January 6, the end of the twelve days of Christmas and the Feast of the Epiphany when the three wise men, those kings of the Orient as they were, brought the child in the straw the gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. It would be a sorry thing if the assault on the US capitol changed our sense of the character which has been burned into us for a large fraction of the time our civilisation has lasted. It’s a reminder that Shakespeare, who kicked off the Christmas season in 1606 with that diverting representation of family life King Lear, wrote his name forever on the last day of Christmas a few years earlier, perhaps in 1601, with one of the very greatest of his so-called happy comedies, Twelfth Night. And those who argue (as many do) that Twelfth Night is the greatest of the comedies, think it is such a great comedy because its lyricism is so tristful, it encompasses so much of the sadness of the world, even as it grabs at every gag. Think of Feste, the clown, alone on the stage at play’s end, singing about how ‘the rain it raineth every day’. Think of how Malvolio, the pompous steward, is baited into imagining that Olivia, the great lady of the estate is in love with him, and cries out when he realises what has been done to him, ‘I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you.’ Think too, of how Olivia herself falls in love with Viola as the boy she pretends to be and Viola says, ‘Dear lady she were better love a dream.’ It’s a romp that encompasses every kind of broken-heartedness. When Sir Andrew Aguecheek, Sir Toby Belch’s foolish drinking companion, a pitiably innocuous man says, ‘I was adored once too,’ we don’t believe it for a moment.

Sir Ian McKellen said once that he felt the same way about Twelfth Night that his Cambridge tutor did when he said, ‘I’m only interested in seeing it performed by archangels.’ What this points to is that Twelfth Night virtually demands that its ensemble of interconnected characters should be the finest actors you can find, even in what look like character roles. It was that unlucky monarch Charles I who scribbled on the text of Twelfth Night that it should really be called Malvolio. I remember back in 2018 talking to an Englishman, a translator from the Spanish, who knew his theatre, about the fact that Geoffrey Rush had withdrawn from Simon Phillips’ production of Twelfth Night and the Englishman said he thought he was the only actor on earth who would be capable of playing Malvolio. It’s certainly a role that has a tremendous weight because it shows the burden of the play’s sense of heartbreak and catastrophe.

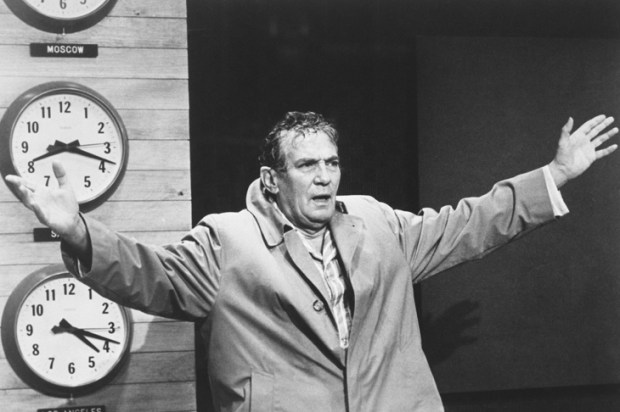

The archangels, of course, have done their best with the extraordinary light and dark patterning of this play. Vivien Leigh in 1961 toured here as Viola and that other Lady Olivier, Joan Plowright, can be seen in one of the starriest of all productions – made for ITV by Granada television in 1968 and directed by John Dexter – in which she doubles as Viola, the girl who discovers she’s in Illyria and as her twin brother Sebastian. This is a production which not only has a ravishing Olivia in Adrienne Corri and a handsome resonant Orsino in Gary Raymond but Ralph Richardson – the greatest Falstaff of his day – as Toby Belch, the old drunk who scoffs at Malvolvio’s lack of appetite for ‘cakes and ale’, and Alec Guinness as the humorless steward (in this case a mellifluous and parsonical one) with that peerless Cockney songster Tommy Steele as Feste the singer-clown who can see the black side to any joke.

But it’s a play which demands the grandest of actors: hence Ben Kingsley as Feste in Trevor Nunn’s film and the rave reviews Mark Rylance got when he played Olivia in a production which had Stephen Fry as Malvolio.

When I felt impelled to revisit Twelfth Night, a play I had seen Judi Dench do 50 years ago with Donald Sinden, I put on the old Caedmon recording which cannot be bettered. The great Irish actress Siobhan McKenna is a keeningly lyrical Viola and Vanessa Redgrave is the perfect complement as a stately desolated Olivia who discovers the dream of love as a deepening of what she imagined was a total sadness. The Malvolio is Paul Scofield – the greatest Lear of the time – and he uses an overreaching would-be refined London accent as the index of the futility of his predicament. He’s sane, he’s sepulchral, and he’s bitterly bewildered by the wrongs that are visited upon him. It’s a thing of wonder that Shakespeare manages to transfigure a storyline that is almost knockabout with such a sense of the complex and heartrending reality of the world and this spoken word recording – which is on Apple Music – is as close as you’ll get to that unearthly sense of the messengers of God giving their voices to Shakespeare’s apprehension of the deep sadness that can colour the idea of life as a joke.

It’s strange how sometimes the sense of the classic, ancient or modern, can sometimes be the best bet. We watched Mike Nichols’ film of Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in sync with a young friend down at the beach and it stood up remarkably well. Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor had a rather more frolicsome time depicting the warfare of married life in Franco Zeffirelli’s film of The Taming of the Shrew and it’s bizarre to hear that the long-ago stars of its companion piece, his ravishing teenage Romeo & Juliet, Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting are now suing because the film includes a glimpse of her bare breasts and his bare bottom. These are, from memory, glimpsed momentarily, in the scene where Juliet says, ‘It was the nightingale and not the lark,’ and Romeo replies, ‘It was the lark, the herald of the morn, and no nightingale.’ This is after Friar Laurence has married them and although it is fringed with the potential tragedy of Romeo’s banishment, is Shakespeare’s one representation of postcoital bliss, and of two kids losing their virginities as newly-weds.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.